Two weeks ago, we talked about the Superhero genre and where it stands today, but I purposefully held off on actually describing the genre. That’s because there’s a lot of ground to cover there.

On the surface, it looks pretty cut and dried. Pretty much anyone can tell a superhero story when they see it. We all know the basic formula just as well as we know that space ships are sci-fi and wizards are fantasy.

And that’s kind of the problem really, and why a lot of the works today generally comprise a feedback loop of nitpicking the same attendant tropes over and over (note: I have been informed since the last article that this isn’t what deconstruction is supposed to be. I stand corrected and wish the people who describe their works that do this would too). To put it simply, people know the basics, never look deeper, and get bored. And bored people are vindictive people (I’m looking at you, Mark Millar).

That people tend not to go deeper is probably why you don’t see a lot of the setting shift I lamented in the last article too: the ‘like New york except where noted’ thing is just taken as a given. Well it’s not and that’s what I’m going to try and dispel.

But first, a word on genre fiction in general (warning, rant ahead):

There is a certain species of person who will respond to hearing that one likes, or heaven forbid, writes genre fiction with the kind of contemptuous sneer most people reserve for someone who just said they just shit their pants, or enjoyed Here Comes Honey Boo-Boo (no power on Earth can make me link that nightmare of a show). Then they tell you that everything in that genre (or any genre) is trash and recommend that you read dense brick of a literary fiction piece that’s as experimental as it is incomprehensible, with the climax on page ten, the end at page twenty, and then seven hundred pages of nothing interesting happening for no good reason.

Now, I don’t begrudge the kind of people who genuinely like lit fic, or experimental books (experiments are how we get cool, new things that will eventually become tomorrow’s tropes and genres, after all.), or who don’t enjoy the kind of fiction I read (this being the internet though, I’m obligated by the Lack of Civil Discourse Act of 2003 to characterize them all as hipster losers). What I do object t is the kind of person that looks down on people for enjoying genre fiction.

I could write an entire article about how books and movies are the only movies with large subcultures expressly opposed to using them expressly for enjoyment, but now is not the time, and I don’t have enough curse words at the moment.

Me, seconds into any lit-fic vs genre fic/oscar bait vs blockbuster discussion.

Somewhere along the way, ‘genre’ started getting taken to mean ‘cliché packed’ which meant ‘not serious’. And remember, serious is the only thing that’s important. To some people; people who will find you if you like to talk about reading a lot online; the act of following genre conventions means that a story can’t possibly be worth a person’s intellectual time.

Well the joke’s on them, gentle reader. Because, genre conventions are a type of rule; a base on which the writer can build and draw inspiration from. And if you’ve been reading this blog a while, that might sound familiar. That’s right, genre conventions are Rules. And as I’ve explained before, rules can be good for you.

So with that out of the way, let’s look at the rules of the Superhero genre.

The Superhero

No. Don’t say ‘duh’. This is an actual, important point. Fantasy and Science Fiction are generally tied to their setting. While yes, you can have fantastic or sci-fi elements intruding on mundane settings, or the most part, these two place high importance on the setting. Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Dragonriders of Pern, The Gentleman Bastard Cycle, Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the list goes on and on and one of the major common treads is that the setting plays a massive part in defining the story. It is the cornerstone and the bedrock of good storytelling in both genres.

Superhero is different. It is defined by the presence of a character type. Obviously, that is the superhero, but it’s not really that clear cut. Not all heroes are heroic, and not all Superhero stories feature this character as a protagonist, or even a major character. And not all of them are all that heroic—or super for that matter.

So just what the heck is a superhero in this case? Well I’m glad you asked, because otherwise, this article would be really short. Let’s break it on down now.

The Super

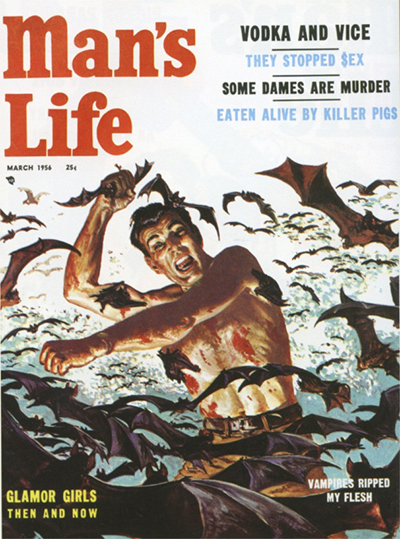

One thing you have to remember is that Superheroes were born out of pulp adventure novels. Back then, badass dudes traveled the world in order to punch it’s finest faces and stab its best and brightest animals.

Proto-Batman, seen here receiving his powers.

These guys were extraordinary, and like all things in creativity, the writers who came next had to top the previous guy. This guy could punch harder and his animal stabbing knife was something fancy like a kris or kukri, which made him better. But no, this guy could also kick! And he used an ax!

Oh yeah? Well this guy uses ancient jungle medicine, and this one knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men.

And so it began. But what all of these superhero precursors, these neander-heroes, if you will, had in common with even those of today was that they all had extraordinary abilities or will that allowed them to deal with their problems in ways a normal person either could not (at least not in a survivable fashion) or would not.

These could come in the form of blatant superpowers, like Superman, a special sense that let them intervene in situations most wouldn’t notice, like the Shadow (who got more powers later), or determination that allows them to accomplish things no one else can (and also all the money), like Batman.

All of them are empowered to an unrealistic extent even when this is presented as ‘mundane’. It’s this aspect that places the genre firmly in spec-fic, as it’s all about stretching the bounds of what we consider normal. Even the guy who solves crime with daily doses of vitamin violence isn’t really something that could happen for long before he’s arrested or killed.

That’s the first step. A superhero is different from others in a way that makes them uniquely able to handle threats and other unusual situations. Which is good because the next step is that…

They Deal with Issues Beyond the Scope of Their Society

Part of the reason Superman even exists is because Seigal and Shuster were two children of the Depression, who saw the corruption and they wished someone could kick the crap out of the people responsible and fix everything (preferably with violence).

In a way, that’s still pretty much the point of Superheroes. They take care of threats bigger than what we as a people feel we can handle. And that can be by proxy, such as the Soviet Union in the form of Omega Red, metaphorical, like the various polluting villains from Captain Planet and the Planeteers, or literal, like the intended result of the evil plan in Watchmen.

Similarly, villains tend to embody those things we can’t handle, or underscore it. Lex Luthor, in the modern age is the glorious, golden god of corporate corruption. Marvel’s Kingpin is the patron saint of the untouchable core of organized crime.

[stock fat joke #1883 not found]

But the metaphor isn’t necessary. The point of this being on the list is that this is the ‘why’ of a superhero. If there aren’t any threats that they’re needed to handle, even if it’s rampant crime the police are too understaffed to stop, why is this person being a superhero? And why do they have…

Alternate Personas

You might notice that I didn’t call this either a secret identity or a costumed identity. This is on purpose.

There’s a lot more to this then just having a secret identity. Much is made about how Clark Kent is the real person and Superman is the mask while Batman is the real one and Bruce Wayne is the mask, but most superheroes tend to fill multiple roles not expected of other people.

A normal person, if they’ll admit it, has a ‘work’ persona and a ‘home’ persona. They might not notice this, but they do, the same way they act and react differently in a formal setting than at a party where kegs are present and abundant. This differentiation is a natural psychological phenomenon and is totally healthy. But Superhero is one of the few genres to feature it so permanently.

Identity is popular with everyone of course, but this particular idea; that the given situation you are in at the moment changes who you are is pretty unique and ubiquitous.

Peter Parker is always concerned with how Spider-man’s actions will affect his life. She-Hulk seems on the surface like Jennifer Walters only buffer and greener, but it turns out that Walters stays in her Hulk form because it gives her an excuse to be outgoing. Both in and out of costume, Drake Mallard (Darkwing Duck) is a bumbler and an egomaniac, but when the ships are down, he gets dangerous.

Nostalgia Powers: Activate!

Whether this identity shift comes with a costume change, there’s never a costume change, or they stay in costume, the duality there is a consistent theme in Superhero stories. Fans of this site might notice that I use real names when the characters are in civilian mode and codenames when they’re being heroic.

I think this might be part of why the genre resonates so well. We all understand this, whether we know it or not, and we don’t really get to see it explored elsewhere.

So now we have a person with spacial capabilities, who faces conflict outside the purview of their society, who had some level of duality to them. That’s a good start, but we haven’t exactly discounted Luke Skywalker, or James Bond, now have we? (By the way, go check out the Skyfall theme [or buy it here]. It’s so Bondy that if you sit in the sweet spot of your surround sound system, a vodka martini and a Walther PPK will appear in your hands)

That’s because I haven’t mentioned…

The Crusade

Yup, I said ‘Superhero’ and ‘Crusade’ in the same article. Go ahead. Get it out of your system.

Feels good, doesn’t it?

So in the last article, I mentioned running a superhero game in The Forgotten Realms. This is the lesson I learned from that experience: Superheroes are not tied to quests.

Allow me to explain: one of the most popular and well known story structures is the Hero’s Journey. This time tested titan of thematic tinkering is the center of many fantasy and sci-fi stories. To put it as simply as possible, it’s a story about a quest that develops character along the way. Frodo did it, Luke did it, Tavi did it a couple of times. There is a clear goal and once it’s done, the protagonist returns home or goes on to their reward.

Most superheroes don’t have this. Yes, they might go on a quest once in a while, but motivation-wise, their prime motivators are goals with no set endpoint. They want to protect something, or up hold justice, or exact vengeance as it comes.

As long as the big problem from my second item is there, they will never be done. Quests, arch-villains, planet killer asteroids; these are all just obstacles in the long and winding path. This is the crusade, and it’s what gives the superhero genre’s individual works their longevity and sense of history.

Even if the story is a stand alone, it tends to be presented in the form of a highlight in a longer career.

In a sense, this makes the Superhero story less about clear resolution and more about ongoing struggle. I almost said victories in an ongoing struggle, but victory isn’t necessary to the story, just the scope of the superhero’s mission.

These four elements come together to form the character archetype that forms the backbone of the genre. That doesn’t mean that such a character is the protagonist, only that the presence of this type of character informs the setting and story.

The exceptional miniseries Marvels (but not it’s terrible and stupid counterpart, Ruins) does this to great effect inside the Marvel Universe itself: showing how the superheroes touch the lives of the ordinary people in the setting, as told through the eyes of one of those ordinary people.

Likewise, the entire Super Hero School sub-genre (which includes PS-238, and my own Liedecker Institute) focuses on institutions that would logically became increasingly necessary in worlds with heavy superhero populations. Typically, the students themselves have powers but are not expected to take on extra-societal threats or engage in crusades, and thus aren’t superheroes as such, but the influence of superheroes is evident.

Another sub-genre, Super-villain, (including the HIVE novels, Megamind and Despicable Me) draw importance from those individuals that supply those extra-societal threats and would necessitate superheroes. Notably, Despicable me doesn’t even feature a single superhero, but the theme and mentality is there, and Grue ends up fulfilling all of the Superhero requirements besides anyway.

And as this is a young, largely unexplored genre, there is plenty of space to develop new directions as well. The path isn’t so well thread as we might think.

And in the next blog, I’ll be talking about ways this genre can be played with that probably not a lot of people had thought of. Until then, folks.